When Aberfan disasterAberfan, Wales struck at 9:15 a.m. on 21 October 1966, a towering wall of coal waste buried Jeff Edwards, then 8, under a slurry‑filled crater that also claimed 115 other children and 28 adults. The collapse was traced to the National Coal Board (NCB), which had sited the spoil tip atop a natural spring despite warnings. Nansi Williams, the school cook, died shielding five pupils, while acting headmaster Kenneth Davies described the blast as a “jet‑plane scream” that turned Moy Road into a landscape of devastation.

What Happened on That October Morning

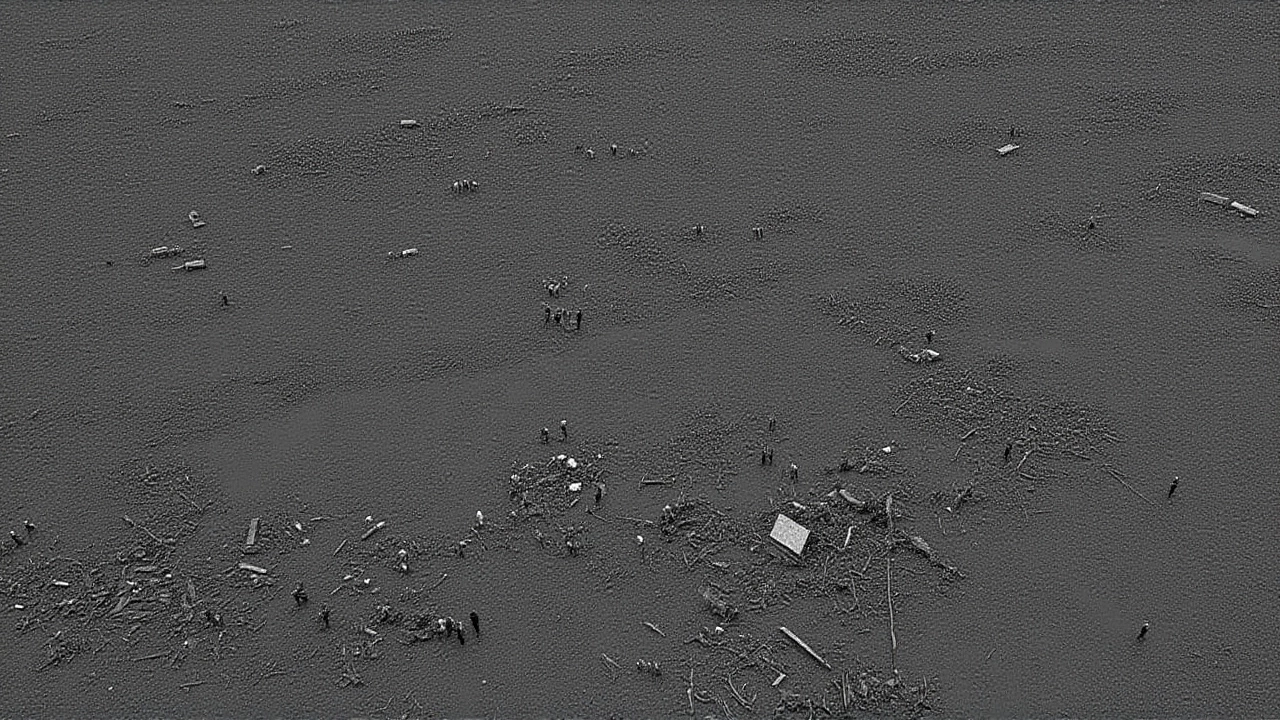

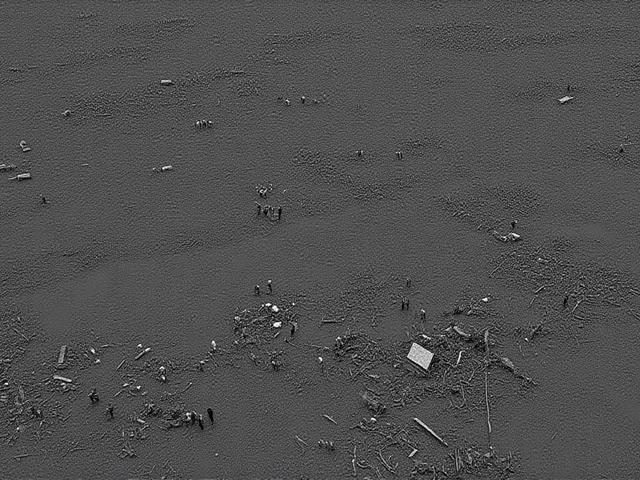

The NCB’s tip, holding roughly 140,000 cubic yards of waste, had been built on saturated ground after decades of mining in the South Wales Valleys. On the fateful morning, a sudden landslide sent the material rushing down the hillside at over 80 mph, forming a 30‑foot high slurry wave that slammed into Pantglas Junior School and the neighboring houses. By 11:00 a.m. rescue crews pulled the last survivor, Jeff Edwards, from the muck. The immediate death toll stood at 144, but the community’s grief would echo for generations.

Immediate Response and Rescue Efforts

Local firefighters, police, and volunteers converged on the scene within minutes. Among them was John Cole, a British Red Cross worker whose daughter later recounted his relentless digging, “shirts off, bodies sweating, even though the air was cold.” The grim task of recovering bodies stretched over two weeks; forensic teams painstakingly identified each victim, a process documented by BBC reporter Ceri Jackson who called the tragedy “a mistake that cost a village its children.”

The Inquiry, Legal Fallout, and Compensation

In the weeks that followed, a public inquiry led by Lord Justice Runciman exposed the NCB’s negligence. The board had ignored safety reports that warned the tip’s foundation was unstable. When the government allocated £850,000 for tip removal – £350,000 from the NCB, the remainder from public funds – the decision sparked controversy. S. O. Davies, a local MP, was the sole dissenting voice on the charity‑fund committee and resigned in protest, later described by political scientists Jacint Jordana and David Levi‑Faur as an “unquestionably unlawful” use of charitable assets.

Long‑Term Health and Psychological Impact

Decades of study reveal a haunting legacy. A 1999 University of Wales survey of survivors found that 29 % still suffered from post‑traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) 33 years later, and 46 % had experienced PTSD at some point, compared with 29 % in a control group of pupils from the nearby secondary school. Survivors reported chronic sleep problems, anxiety, enuresis, and a profound sense of survivor’s guilt. One former pupil recalled, “We didn’t go out to play for a long time because those who’d lost their own children couldn’t bear to see us.”

Medical records from the village showed a spike in mortality among close relatives of the victims – a seven‑fold increase in the first year after the disaster. A local doctor summed it up succinctly: “By every statistic – patients seen, prescriptions written, deaths – this is a village of excessive sickness.”

Legislative Changes and Legacy

The tragedy forced a complete overhaul of tip safety. In 1969 Parliament passed the Mines and Quarries (Tips) Act 1969, followed by detailed regulations in 1971 that set standards for tip construction, monitoring, and inspection. Those rules remained untouched until the comprehensive Mines Regulations 2014, which retained the core stability provisions born of Aberfan’s lessons.

Even the environment felt the aftershocks. In August 1968, heavy rain washed residual slurry down the village streets, a stark reminder that danger lingered. Yet, paradoxically, the birth rate in Aberfan rose sharply in the five years after the disaster, contrasting with the declining trend in the broader Merthyr Tydfil area.

Remembering the Victims

Each year, a memorial service draws former residents, officials, and schoolchildren to the site. The original school building was never rebuilt; instead, a community center now stands, housing plaques that list the names of the 144 victims. The story continues to inspire artistic works, documentaries, and academic research, ensuring that the lessons of Aberfan remain part of the national consciousness.

Future Implications and Ongoing Research

Recent investigations into other spoil‑tip sites across the UK cite Aberfan as the benchmark for risk assessment. Scholars argue that while the immediate legal reforms were groundbreaking, the psychological care for survivors set an early example for trauma‑informed public health responses.

As the village approaches its 60th anniversary, activists call for a formal apology from the successor of the NCB, now part of British Coal Operations Ltd., and for a new fund to support the aging survivors who still battle chronic health issues.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why did the Aberfan spoil tip collapse?

The tip was built on a natural spring without proper drainage. Heavy rain saturated the waste, destabilising the mound and causing the 1966 landslide.

How many children survived the disaster?

Only eight children initially survived the slide; the last, Jeff Edwards, was rescued at 11 a.m. All other pupils at Pantglas Junior School perished.

What legislation was introduced because of Aberfan?

The Mines and Quarries (Tips) Act 1969 and the accompanying 1971 Regulations set strict standards for tip construction and monitoring, later incorporated into the Mines Regulations 2014.

Did any survivors develop long‑term health problems?

Yes. Studies show elevated rates of PTSD, sleep disorders, anxiety, and a seven‑fold increase in mortality among close relatives during the first year after the tragedy.

Has anyone sued the National Coal Board for the disaster?

Despite the obvious negligence, no survivor or family member has successfully brought a lawsuit against the NCB or its successor companies.

Why Some People Miss Their State Pension at 66 – Explained by Expert Steve Webb

Why Some People Miss Their State Pension at 66 – Explained by Expert Steve Webb

Is drag racing actually racing?

Is drag racing actually racing?

Messi nets two in tearful Buenos Ayres farewell as Argentina beat Venezuela

Messi nets two in tearful Buenos Ayres farewell as Argentina beat Venezuela

RFU Backs Tom Curry Amid Contepomi 'Bully' Accusation After Twickenham Clash

RFU Backs Tom Curry Amid Contepomi 'Bully' Accusation After Twickenham Clash

Aberfan Disaster: 1966 Tragedy, Aftermath and Lasting Legacy

Aberfan Disaster: 1966 Tragedy, Aftermath and Lasting Legacy